India’s Electricity Distribution Turnaround: Real Progress or Statistical Mirage?

For most Indians, electricity is like air: invisible in its presence and intolerable in its absence. Every summer, conversations about “load-shedding” and “power cuts” resurface with ritual regularity. Yet far from being just a matter of supply and demand, India’s electricity challenge has long been a story of distribution inefficiency, chronic financial stress and distorted incentives. Recent government data suggesting that India’s power distribution companies (DISCOMs) have returned to profit for the first time in over a decade is promising, but deeper analysis highlights how much has changed — and how much has not.

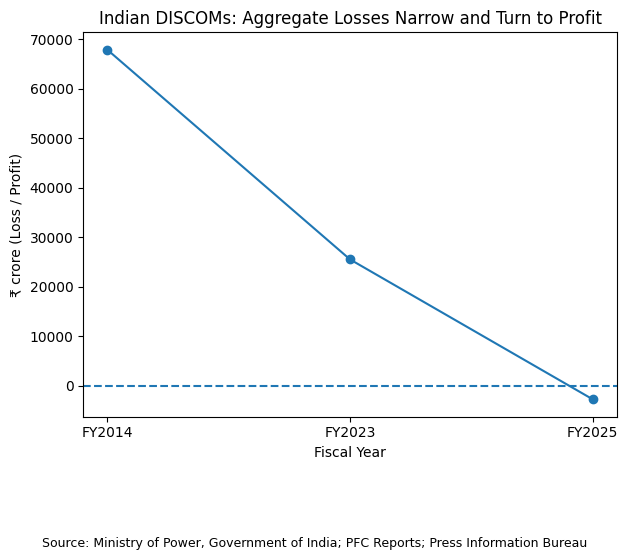

Under the Ministry of Power’s official accounting, the combined profit after tax (PAT) of all DISCOMs and state power departments stood at ₹2,701 crore in fiscal 2024–25. This is a remarkable reversal from a ₹25,553 crore loss in FY2023–24 and the far larger ₹67,962 crore loss in FY2013–14.

At first glance, this turnaround feels historic. But the real story lies not in a sudden magical fix, but in a decade of complex policy reforms, enforcement of financial discipline and urgent infrastructural upgrading. Even then, structural problems persist — and the forthcoming Electricity Amendment Bill currently before India’s Parliament promises deeper changes.

Why India’s Electricity Woes Were Never About Generation

India today stands as the third-largest electricity producer in the world, with total generation exceeding 1,800 terawatt-hours in FY2024–25. Around 25% of this comes from non-fossil sources — a reflection of ambitious renewable expansion. Private participation has grown steadily since the Electricity Act of 2003 liberalised generation.

Yet generation was never the binding constraint. Power plants have been able to meet rising demand, and India’s capacity has steadily expanded. The issue has always been the “last mile” — the engines that turn electrons into usable power and then convert consumption into revenues: the DISCOMs.

DISCOMs, mostly state-owned, are legal monopolies in their service areas. They buy power from generation companies, deliver it to consumers, bill for it and collect money. Each link in that chain was historically broken: transmission losses were high; billing was inefficient; tariffs were often set below cost for political reasons; subsidies were opaque; and payments to generators were delayed without consequences.

This dysfunction was visible in the numbers: between 2017–18 and 2020–21 alone, cumulative losses of DISCOMs exceeded three lakh crore rupees.

The Turnaround: Reforms Under the Hood

Recognising that perennial bailouts could not be the long-term solution, policymakers over the past decade launched a series of reforms aimed at structural correction rather than ad-hoc financing.

1. Revamped Distribution Sector Scheme (RDSS)

Introduced with a multi-year budgetary outlay exceeding ₹3 lakh crore, the RDSS was designed to condition future central funding on DISCOM performance — especially reducing technical and commercial losses, narrowing the gap between cost and realization, and improving billing and collections. The approach was explicitly results-linked: modernise infrastructure and smart metering systems, improve operational efficiency and tighten accounting transparency — or forgo access to funds.

2. Late Payment Surcharge Rules

For years, late payments were treated as an inconvenience. DISCOMs delayed payments to generators; government departments delayed subsidy reimbursements; consumers delayed bill settlement. The new Electricity (Late Payment Surcharge) Rules made penalties automatic and enforceable, discouraging chronic default. Combined with tighter payment discipline, this helped reduce outstanding dues to generators by 96% — from over ₹1.39 lakh crore in 2022 to under ₹5,000 crore by January 2026. Payment cycles, once at 178 days, contracted to 113 days.

3. Improved Operational Indicators

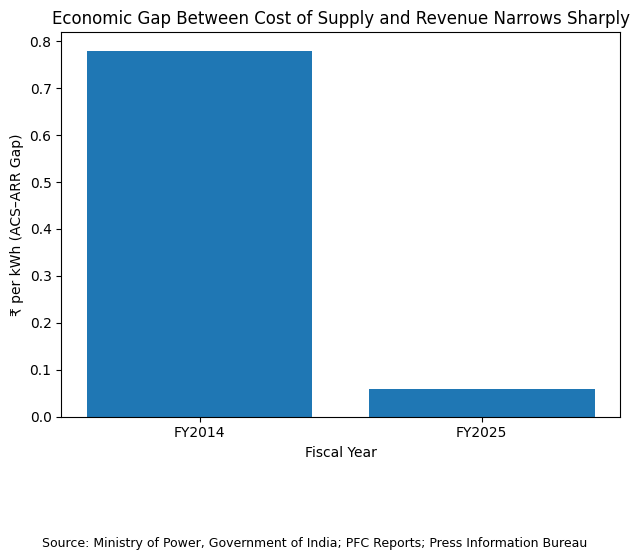

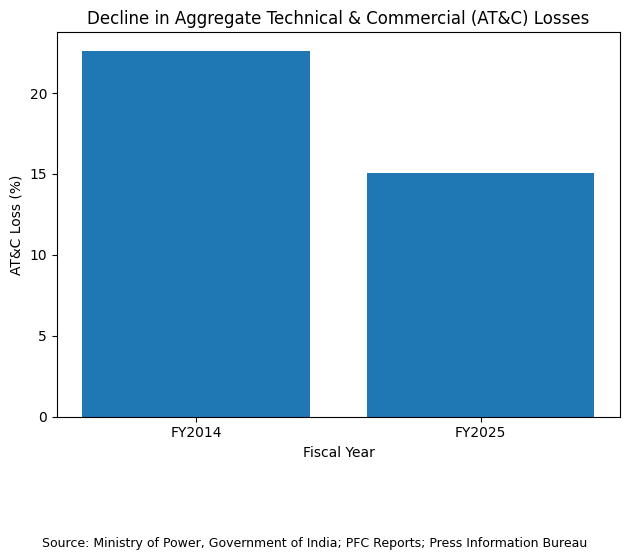

Two metrics are central to distribution economics:

- Aggregate Technical and Commercial (AT&C) losses — a composite measure including line losses, theft, billing errors and collection shortfalls.

- Average Cost of Supply–Average Revenue Realised (ACS–ARR) gap — a measure of how much DISCOMs lose per unit when the cost of power supply exceeds realised revenue.

Between FY2013–14 and FY2024–25, AT&C losses declined from 22.62% to 15.04%, and the ACS–ARR gap shrank from ₹0.78 per kilowatt-hour to just ₹0.06.

These are not trivial improvements. They reflect better operational practices, stronger enforcement and, increasingly, the adoption of smart meters that reduce theft and improve billing accuracy.

Behind the Headlines: What Profit Really Means

The recent profit figure has been widely covered — including commentary by the Union Power Minister calling it a “new chapter” for the distribution sector. But veteran observers know that philosophical payoff and statistical profit are not identical.

Collective profitability masks considerable variation across states. Official data, and analysis by independent sector trackers, show that around 50 DISCOMs remain loss-making even as the sector overall swings to black. Moreover, profits on aggregate accounting do not automatically translate into sustained structural efficiency:

- Smart metering and network upgrades are uneven across states.

- Subsidy design and timing of reimbursements remain contentious political issues.

- Independent Regulatory Commissions sometimes delay tariff adjustments, prolonging revenue shortfalls. For example, in Delhi — one of India’s most advanced power markets — the regulatory body has delayed tariff revisions since 2014, despite rising power purchase costs.

In such instances, DISCOMs may accumulate regulatory assets — deferred costs that regulators permit to be recovered later — but these do not vanish from the ledger.

The Electricity Amendment Bill: A Turning Point?

Arguably the most consequential policy initiative on the horizon is the Electricity (Amendment) Bill, which has been under deliberation since its introduction in 2022.

The Bill proposes deep changes:

- Introduction of consumer choice and competition, breaking the monopoly of distribution licensees in given areas.

- Enabling independent distribution companies — entities that supply power without owning physical lines — to compete on price and service.

- Strengthening the role of state and central regulators in tariff setting and dispute resolution.

Proponents argue that competition and market mechanisms will discipline costs, attract private investment and spur innovation. Critics caution that without careful safeguards, competition could fragment networks, undercut cross-subsidy structures and expose vulnerable consumers to higher prices.

As a seasoned economist, I believe a calibrated, phased approach is essential. Competition should be introduced where feasible, but basic infrastructure and state capacity must be strengthened first. Transitional support for states with high pre-existing AT&C losses and poor financial health will be necessary to ensure equity and social goals are preserved.

Remaining Risks and the Road Ahead

Even with recent gains, significant risks endure.

1. Political Economy of Tariffs

Electricity tariffs remain politically sensitive. Frequent delays in tariff revision — whether in populous states or metropolitan regulatory regimes — can erode margins and reintroduce losses. Effective regulator independence is vital.

2. Regional Disparities

Performance varies sharply across states. Some, like Goa or Gujarat’s urban utilities, have achieved low AT&C losses and strong collections; others lag far behind. A one-size-fits-all reform roadmap will not suffice.

3. Infrastructure Investment

While the RDSS and central funding provide incentives for grid upgrades and smart metering, capital investment must continue beyond these programmes. Distribution networks need reinforcement to cope with rising demand, especially from electrification of transport and industry.

4. Demand Growth

India’s electricity demand will continue to rise rapidly. Sustaining reliability requires not just financial discipline, but strategic planning, load management and integration of intermittent renewable generation.

Conclusion: Real Progress, Conditional Durabilit

There is no doubt that the recent collective DISCOM profit is a milestone. It reflects a decade’s worth of policy reforms, structural discipline, and painstaking operational improvements. But it is not, in itself, proof that all distribution sector ailments have vanished.

The profit is a signal, not a destination — an indicator that incentives, enforcement and good governance can reshape even the most troubled public utility sector. India’s policymakers now face the task of translating one year of profit into a durable, sustainable model that balances affordability, equity and financial resilience.

The Electricity Amendment Bill, if carefully structured and intelligently phased, could provide the legal backbone for deeper transformation. But abandoning the hard work of infrastructure strengthening and regulatory maturity in favour of premature competition would be a strategic error.

If recent reforms have proven anything, it is that discipline and accountability — not bailouts — create sustainable value. India’s summer ahead may yet be brighter, not because the wires hum uninterruptedly, but because the sector that powers them finally found its feet.

Reference:

https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2215761®=3&lang=2

https://prsindia.org/billtrack/the-electricity-amendment-bill-2022

https://powermin.gov.in/sites/default/files/uploads/Final_Revamped_Scheme_Guidelines.pdf