Economics

Environment

Policy

Climate Adaptation, Climate and Growth, Climate and Public Policy, Climate Change, Climate Change and Economy, Climate Economics, Climate Finance, Climate Governance, Climate Resilience, Climate Risk, Climate Risk Management, Economic Resilience, Energy Transition, Environmental Policy, Extreme Weather, Global Warming, Sustainability

AnilMehta

The Climate Ledger: What the Last Year (2025) Revealed — and What the Next One (2026) Will Demand

By any serious economic or environmental accounting, the past year has closed the debate on whether climate change is a future problem. It is now a present-tense economic force, reshaping growth trajectories, fiscal balances, public health, and geopolitical stability. What once appeared as environmental “externalities” have moved decisively onto national balance sheets.

The last 12 months did not introduce new climate dynamics; rather, they exposed how far the world has already drifted from climatic stability. Extreme heat, volatile rainfall, forest fires, food-system stress, and energy insecurity were not anomalies but symptoms of a system operating beyond its historical range. For policymakers, investors, and citizens alike, the question is no longer whether the climate is changing, but whether governance systems are adapting fast enough.

A Year That Confirmed the Trend

The most striking feature of the past year was not the severity of individual climate events, but their simultaneity. Heat waves overlapped with water stress; floods arrived in regions previously accustomed to drought; fires erupted outside traditional fire seasons. These compounding shocks amplified economic losses far beyond the immediate damage.

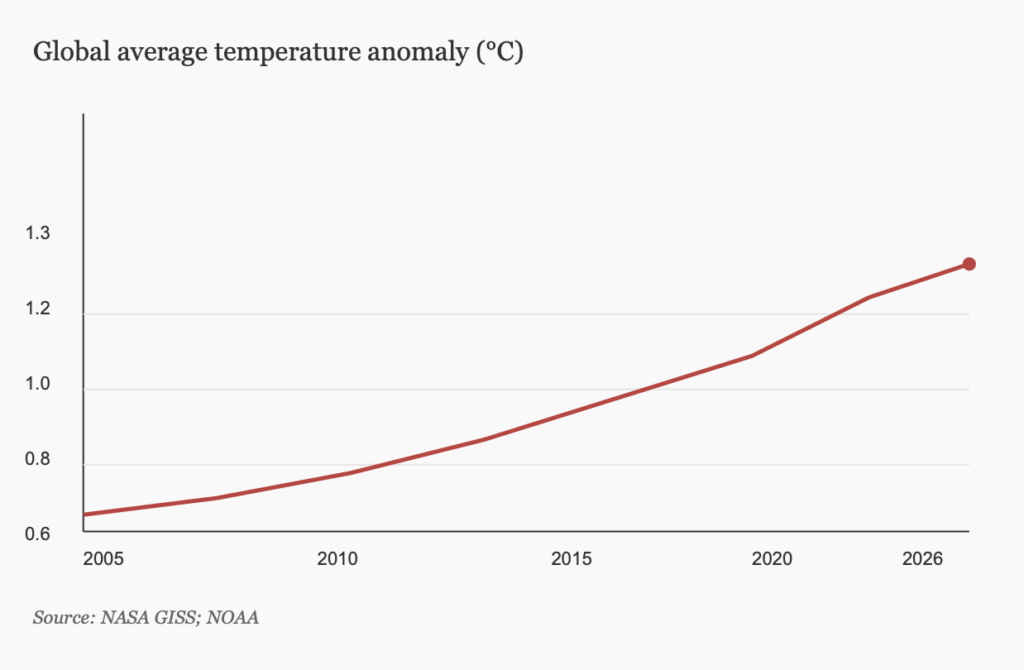

Global temperature data shows why. Average global temperatures have risen steadily since the mid-2000s, pushing the planet perilously close to the 1.5°C threshold. The past year sits squarely within this accelerating trend, not above it. What matters is the new baseline: extreme events now unfold on top of already elevated temperatures, increasing their intensity and duration.

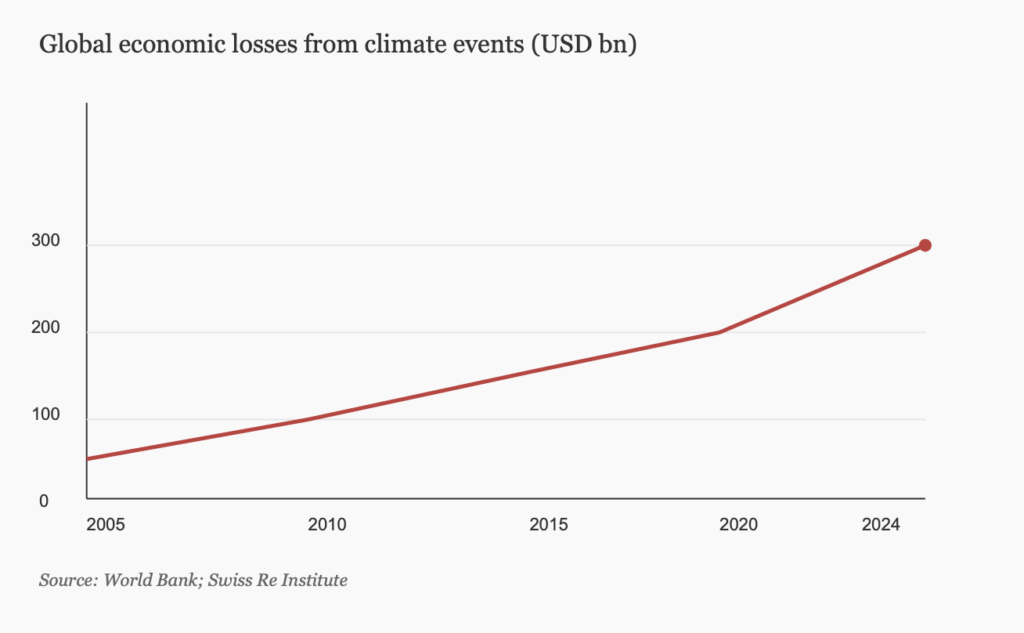

This has direct economic consequences. Global losses from climate-related disasters have climbed sharply over the last two decades, as shown in Figure. These are not abstract costs. They translate into destroyed infrastructure, lost productivity, disrupted supply chains, rising insurance premiums, and mounting fiscal pressure on governments. Emerging economies, with higher exposure and thinner buffers, bear a disproportionate share of the burden.

Urban centres have become particularly vulnerable. Heat stress now regularly overwhelms energy grids and public health systems, while polluted air stagnates longer under warming conditions. In parallel, ecologically sensitive regions — once considered climate refuges — are experiencing destabilisation through erratic rainfall, landslides, forest fires, and retreating glaciers. The old distinction between “developed” and “fragile” geographies is eroding.

Two Decades of Warnings, Largely Ignored

Seen in isolation, the past year appears dramatic. Seen in context, it is merely the continuation of a twenty-year trajectory that economists and climate scientists have documented with increasing clarity.

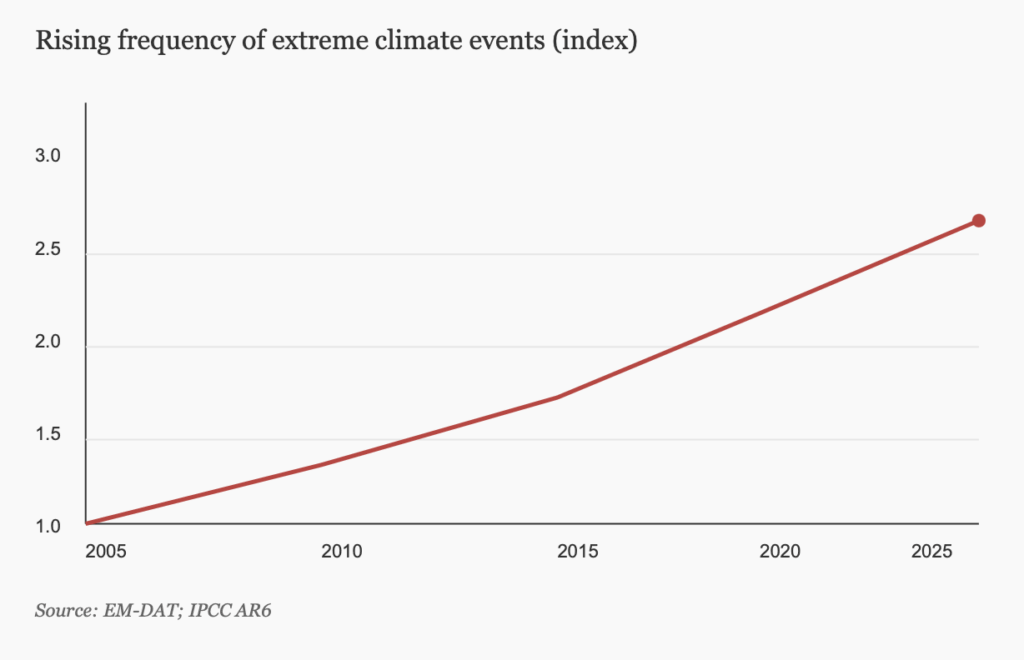

Since the early 2000s, climate risks have shifted from low-probability, high-impact events to high-probability, system-wide disruptions. The frequency index of extreme weather events, shown in Figure , has nearly tripled over this period. This matters more than record-breaking headlines. Frequent shocks prevent recovery, erode capital stock, and trap regions in cycles of reconstruction rather than growth.

Economically, this has profound implications. Climate volatility acts as a tax on development. It raises the cost of capital, discourages long-term investment, and forces governments to divert resources from productivity-enhancing investments to disaster response. Studies now estimate that climate impacts already shave multiple percentage points off national GDP in highly exposed economies — a drag that compounds over time.

Agriculture illustrates the danger vividly. Heat stress, erratic rainfall, and shifting pest patterns are undermining crop yields and food security simultaneously. When food systems destabilise, inflation follows, household resilience weakens, and political stability comes under strain. Climate change, in this sense, is not only an environmental crisis but a macroeconomic and social one.

Climate and Conflict: A Dangerous Feedback Loop

The past year also underscored the tightening link between climate stress and geopolitical instability. Armed conflicts have disrupted energy markets, slowed the transition away from fossil fuels, and redirected public spending toward defence rather than resilience. In response, several countries have doubled down on domestic fossil fuel production in the name of energy security, locking in emissions for decades.

This creates a feedback loop. Climate change intensifies resource scarcity and displacement, increasing the risk of conflict. Conflict, in turn, delays climate action and accelerates environmental degradation. The result is a world that is simultaneously hotter, more volatile, and more fragmented.

What the Coming Year Will Demand

Looking ahead, the next year is unlikely to bring climatic relief. With global temperatures remaining elevated, the probability of further extreme events is high. What will determine outcomes is not the weather itself, but the quality of response.

Three priorities stand out.

First, adaptation must move from the margins of policy to its core. Climate-resilient infrastructure, heat-ready cities, water-secure agriculture, and early-warning systems are no longer optional investments. They are essential to protecting economic stability.

Second, climate risk must be priced accurately. Financial systems still underestimate exposure to physical climate risks. Without proper disclosure and pricing, capital will continue to flow into vulnerable assets, increasing the scale of future losses.

Third, climate policy must be insulated from short-term geopolitical shocks. Energy transitions delayed by conflict today will impose far higher costs tomorrow. Strategic autonomy in clean energy is not only an environmental imperative but an economic and security one.

A Narrowing Window

The lesson of the past year — and indeed the past two decades — is sobering but clear. Humanity has entered an era where climate stability can no longer be assumed. Economic models built on historical climate norms are increasingly unreliable guides to the future.

Yet there is still agency. The same data that charts rising temperatures and losses also points to where intervention matters most. Investments made now in resilience and decarbonisation yield compounding returns; delays generate irreversible costs.

The climate ledger is already being written. The only question that remains is whether the coming year marks the beginning of a serious course correction — or another entry in a growing account of avoidable loss.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Sixth Assessment Report

- NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), Global Temperature Data

- World Bank, Climate Change and Development

- Swiss Re Institute, The Economics of Climate Risk

- EM-DAT International Disaster Database

- Reuters, Sustainable Switch: Climate News Wrap 2025

- Livemint, Climate Change and India’s Economic Future

- FAO, Climate Impacts on Global Food Systems